An American flag isn’t seen in Oppenheimer, Christopher Nolan’s three-hour bio-epic about the embattled physicist who led the Manhattan Project, until well after the first atomic bomb has been theorized to the nth degree, its ethical implications debated, its raw materials assembled, as if any other country could ever marshal the rationalized mania and military resources necessary to construct, test, and deploy what was, at least for its era, the ultimate weapon of mass suffering and death. Hollywood today operates by a similar principle: billions of better-spent-elsewhere dollars go into the machine, incalculable waste and stupefaction comes out. In the 21st century, no moviegoer needs to see a red, white, and blue flag to understand that Oppenheimer, helmed by a British writer-director and starring an Irish actor, is an American story. You just have to listen, in the theater, for the applause that follows the annihilative explosion.

Oppenheimer, as an exercise in pseudo-high-minded populism, does play both sides of the studio system field; it delivers on the face-melting pyrotechnics promised by its subject matter while still, with the trademark Nolan clunkiness, insisting that it is more preoccupied with whimpers than with bangs when it comes to the end of the world. Like Dunkirk, Nolan’s earlier deconstructed World War II drama, Oppenheimer undertakes a formalist re-staging of a well-trod chapter from popular history, removing the expected waymarkers of date designations and location tags until time and place, cause and effect, have collapsed in on themselves, taking with them the linear triumphal narratives often imposed by conquering armies (and by writers who know how to effectively structure a screenplay). As in Nolan’s other largest-canvas genre experiments (Inception, Interstellar), the blockbuster heroism and action are granted equal face time as turgid existential musings about familial duty, unchecked technology, and the faultiness of memory. His films stumble but stop short of fully losing their momentum, mostly because they never sacrifice the A/V spectacle of waves as wide as continents and city neighborhoods that unfurl like Fruit Rollups.

At the start, end, and middle of Oppenheimer, the bombs have and haven’t fallen on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and we trace and un-trace their nonlinear hopscotch construction through a fractured J. Robert Oppenheimer, a Schrödinger’s Scientist who is simultaneously an ambitious young student, a wrinkled footnote on the verge of obsolescence, and a leader of men in his physical and intellectual prime. Once again, we have been prompted to set our watches to Nolan Standardized Time, a chronologically liminal zone where plot, like hot geopolitical conflicts and the air-conditioned bureaucracy that sustains them, doesn’t proceed in a comprehensible fashion. In this way, Oppenheimer functions as an inversion of the high octane nesting doll set pieces of Dunkirk, the film deprioritizing the battlefield to flit energetically between the inert, colorless spaces where wars actually happen. We are constantly in drab conference rooms filled with anonymous suited men, the powerbrokers whose circuitous conversations decide how civilization will stagger backwards or, more rarely, lurch ahead.

Twelve feature films into his career, the result of Nolan’s sophomoric preoccupation with time, along with his hallmarks of muffled dialogue and reflections on misunderstood genius, makes for yet another film whose “complex” surface arguments feel shallow while its compelling (and seemingly accidental) subtexts howl out for interpretation. Nolan seems convinced that he is a filmmaker of the superego, while the text itself brims with a repressed, borderline deviant id. It is this enduring tension between Nolan’s intricately planned intentions and his fumbling execution, perhaps more so than the meticulous craft and project management on display, that has elevated and limited his work since Following, his 1998 debut.

Twenty-five years removed from that promising, emotionally stunted film, Nolan is a genuine auteur with every dollar and technology and privilege at his disposal, and all he needs to do is tell a simple human story, but he remains fundamentally incapable of doing so, even hostile to doing so. (See: the weirdly distant, almost theoretical sex scenes in Oppenheimer.) While Nolan has proven that he can split the atom while navigating a black hole, it seems doubtful that his wooden characters will ever talk or move or desire in a manner that resembles actual, red-blooded life. The humanity in his movies is everywhere concealed despite this clear yearning for understanding, feeling, connection; it is omnipresent yet always out of frame, a globally operative psychological defense mechanism stymying vulnerability on 1,700 IMAX screens all at once. Oppenheimer, depending on whether you find these shortcomings infuriating or endearing, could qualify as Nolan’s magnum opus, or the most damning work yet from an artist who fetishizes knowledge but will never learn the most basic truths about being alive.

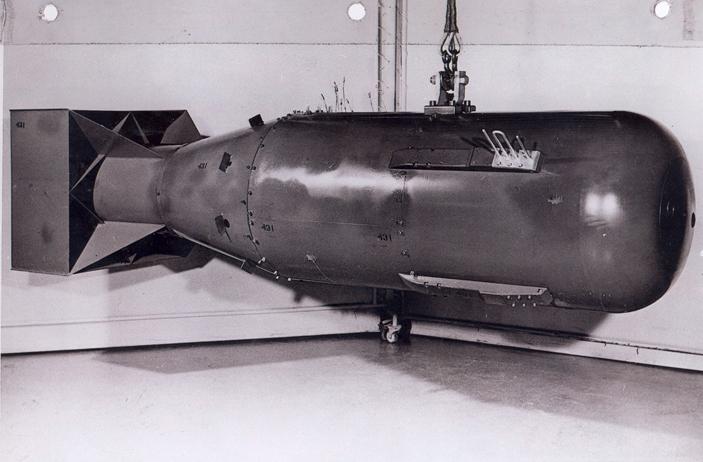

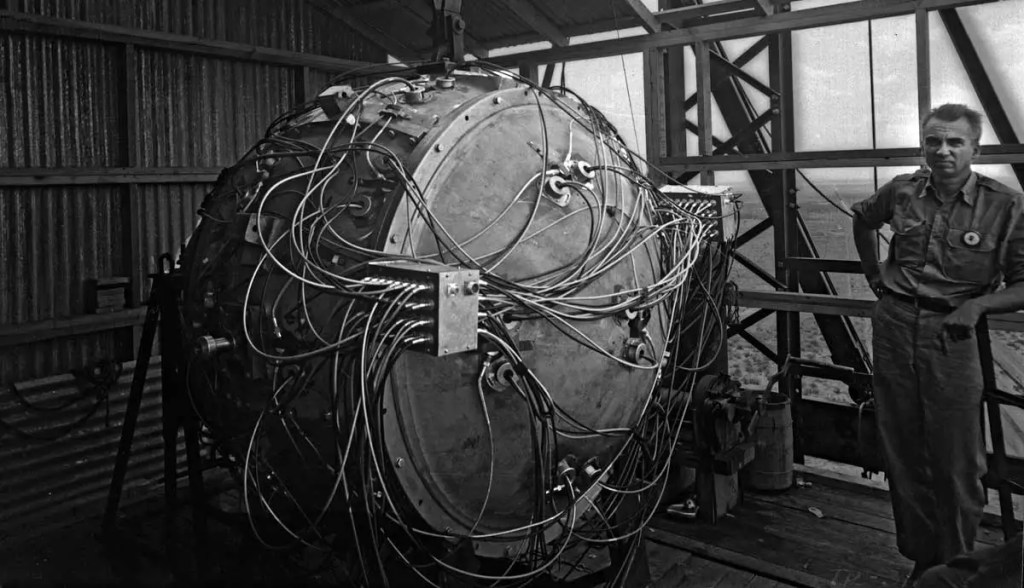

Regardless, Nolan’s delusional commitment to this deranged, ponderous, somehow commercially viable approach to filmmaking deserves attention at the least (and concern for the mental health of society at the worst). Once again, he has charged his philosopher-king directorial proxy (Oppenheimer) to build a hermetically sealed world-within-a-world (Los Alamos) where the realization of an improbable technological feat (the creation of the Atomic Bomb) depends on a ragtag team of straight men with the most homosocial bonds imaginable. Women and minorities, in the tried and true Nolan fashion, are either dead, peripheral, or set dressing–but is that a longing for a white patriarchal past, or well-researched historical accuracy, or Nolan smartly steering away from what he cannot comprehend, which is to say people who don’t look or think like him? All these readings are justifiable, arguably. What cannot be debated is how fucking cool it is when Oppenheimer builds his little team and they drop that bomb in the middle of the desert.

What’s most remarkable about the sequence in which the atom bomb is tested, aside from the crew’s reported overwhelming reliance on miniatures and practical effects, is how much silence Nolan packs into where terrible, essence-shaking noise should be. From Oppenheimer‘s schlocky, Beautiful Mind-y opening scenes through to its overlong courtroom drama third act, we are given intrusive fleeting hints of what a world-ending explosive device might sound like, a sort of nails-on-the-chalkboard-of-space-time motif, but when it finally arrives the detonation is quiet, not loud, a randomized series of whirs from oblivion instead of a single cascading, cathartic blast. The sounds belong neither to reality nor fantasy, the real world nor cinematic one; they are spectral, supernatural, occult. You may not hear them again until death itself passes over your body, carrying your soul away like a fish in a trawl.

Something far, far louder than an atomic bomb, however, is the cheering and clapping and feet stamping when Oppenheimer returns to Los Alamos as a shellshocked hero convinced that he has committed the worst conceivable sin in history. Looking into his crowd of admirers, he watches the heat from an imagined nuclear blast peel the skin from the skull of a beautiful woman, much as the atomic bombs would do to the more than 100,000 Japanese civilians they incinerated, irradiated, and killed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Of course the genocidal consequences of Oppenheimer’s invention must be presented in the context of the same fantasized American vulnerability that facilitated the Korean War, Vietnam, the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan. To have a scene in Oppenheimer that depicts what happened in Japan would wrongfully suggest that, 80 years after the fact, Americans have even started to reckon with what was done (and continues to be done) in their name.

Though Nolan may have built his brand on being the confused man-child of Steven Spielberg and Stanley Kubrick, the director he shares the most spiritual DNA with may be Wes Anderson, his fellow neuro-divergent Gen-Xer. Though Oppenheimer will forever be linked to Greta Gerwig’s BARBIE due to their shared release date, the film’s more interesting companion piece is Asteroid City, Anderson’s mid-century ensemble science fair quarantine drama. Both films return to an age of American exceptionalism and techno-optimism, a period when, dissimilar to our present moment of digital addiction and declining empire anxieties, intelligent people could earnestly believe that technology could end wars, unite countries, and ease the griefs that have hounded our species since hunting and gathering. Nolan’s superior film rightly ends on a sour note because it’s less about the misused tech itself than the paranoia and division that it would foster, the Cold War status quo that persists in a mutated, progress-preventing form to this day.

To steal a line from Wes Anderson, Christopher Nolan is especially not a genius, yet he is smart enough to acknowledge–and to mourn–the fact that Americans can only muster a true communal spirit when it comes to enacting violence, either on ourselves or on other nations. And if you knew that the world’s most powerful country, much like Hollywood’s most powerful director, would likely never admit its mistakes and grow, might you not want to build a bomb big enough to change things? After all, what’s the worst thing that could happen? You could destroy the universe, yes. Or worse: You could accomplish what was once thought impossible and still be yourself.

Final Strawberry Verdict: 4.5 Strawberries out of 5